Mithila Art Unveiled: The Traditional Handmade Painting Technique That’s Captivating the World

In an age of digital art and mass production, there’s something profoundly moving about art that requires human hands, natural materials, and generations of inherited knowledge. Mithila Art, also known as Madhubani painting, embodies all of these qualities. Born in the villages of Bihar’s Mithila region and nurtured through centuries by women who painted their homes and hearts onto walls, this traditional handmade painting form has evolved from a regional folk tradition into an internationally celebrated art movement. Today, as the world rediscovers the value of authentic craftsmanship, Mithila painting stands as a testament to the enduring power of traditional art forms to inspire, connect, and transform.

Understanding Mithila Art – More Than Just Painting

Mithila Art encompasses far more than the paintings themselves—it represents an entire cultural philosophy about beauty, spirituality, and community. The term “Mithila” refers to the ancient kingdom that once spanned what is now northern Bihar in India and parts of southern Nepal. This region’s rich cultural heritage, deeply rooted in Hindu mythology and rural traditions, provides the foundation for understanding traditional Mithila painting.

While Mithila Art and Madhubani painting are often used interchangeably, Mithila Art technically encompasses a broader range of cultural expressions from this region, including painting, pottery, and other folk crafts. However, the handmade paintings are undoubtedly the most recognized expression of Mithila’s artistic tradition. These paintings are known internationally by both names, with “Madhubani” referring specifically to the district in Bihar where the art form was first brought to wider attention in the 1960s.

The cultural context of Mithila painting is inseparable from the lives of Mithila’s women. For centuries, creating these paintings was an essential part of a woman’s education in the region. Mothers taught daughters not just how to paint but how to read the symbolic language embedded in traditional motifs. This knowledge was passed down as part of preparing young women for marriage, with the understanding that they would one day paint the Khobar Ghar—the sacred bridal chamber—for their own daughters’ weddings.

Traditional Mithila painting served ceremonial and ritualistic purposes. Women painted their homes’ walls during festivals like Diwali and Durga Puja, during birth celebrations, and most elaborately during weddings. These weren’t casual decorations but sacred acts believed to bring prosperity, fertility, and divine blessings. The paintings of the Khobar Ghar, in particular, were filled with tantric and fertility symbols, geometric patterns representing cosmic principles, and depictions of gods and goddesses blessing the union.

Contemporary Mithila Art has evolved while maintaining its traditional roots. Today’s artists continue using handmade techniques and natural materials but increasingly explore modern themes—social issues, environmental concerns, women’s empowerment, and abstract concepts—while retaining the distinctive visual language of Mithila painting. This evolution has not diluted the tradition but rather demonstrated its vitality and relevance to contemporary life.

From Village Walls to Global Galleries: Mithila Art Today

The journey of Mithila Art from the walls of Bihar’s villages to international art galleries is a remarkable story of cultural preservation, adaptation, and recognition. For centuries, traditional Mithila painting remained largely unknown outside its home region, practiced by women as part of their domestic and ceremonial duties rather than as “art” in the commercial sense.

The transformation began in the 1960s when a severe drought struck Bihar. William G. Archer, a British civil servant and art historian stationed in the region, suggested that the women artists could earn income by creating their traditional paintings on paper rather than walls. The All India Handicrafts Board and various NGOs helped organize the artists, provide materials, and connect them with markets. This transition from wall art to portable handmade paintings allowed Mithila Art to reach national and eventually international audiences.

Traditional uses of Mithila painting continue in many villages. The Khobar Ghar ritual remains central to wedding celebrations, with families commissioning elaborate paintings to decorate the bridal chamber. During festivals, particularly Durga Puja and Diwali, women still paint their courtyard walls with traditional motifs, refreshing these decorations annually. Birth celebrations, naming ceremonies, and other life milestones are marked with specific Mithila Art motifs believed to bring blessings and protection.

However, the evolution to collectible handmade pieces has profoundly impacted both the art form and the artists. What was once ephemeral—paintings on walls that would fade and be repainted the following year—became permanent. This shift encouraged artists to develop more complex compositions and refine their techniques, knowing their work would endure and be judged by audiences beyond their immediate community. The traditional handmade process remained essentially unchanged, but the artistic ambition and scope expanded.

Contemporary Mithila artists are increasingly exploring themes beyond traditional religion and folklore while maintaining the distinctive visual language of traditional Mithila painting. Some address social issues like women’s education, environmental conservation, and caste discrimination. Others experiment with abstract compositions, using the geometric patterns and color palettes of Mithila Art to create non-representational works. Still others blend Mithila techniques with other art forms, creating fusion styles that speak to younger, global audiences while respecting traditional roots.

International recognition has transformed the status and economic prospects of Mithila Art. Major museums worldwide, including the Museum of Folk Art in New York, the British Museum in London, and various institutions in Japan and Europe, have acquired traditional handmade Mithila paintings for their permanent collections. This institutional validation has elevated Mithila Art from “craft” to “fine art,” with corresponding increases in market value and cultural prestige.

Several Mithila artists have achieved individual fame, becoming cultural ambassadors for Bihar and Indian folk art. Sita Devi, who received the Padma Shri award in 1981, is credited with bringing Mithila painting to national prominence. Ganga Devi, another Padma Shri recipient, was known for her innovations while respecting tradition. These and other master artists have inspired younger generations to pursue Mithila painting professionally, ensuring the tradition’s continuity.

The role of social media and online marketplaces in amplifying Mithila Art’s reach cannot be overstated. Platforms like Instagram, Facebook, and Pinterest allow artists to showcase their handmade work to global audiences instantly. Online marketplaces enable direct sales from Bihar’s villages to collectors worldwide, bypassing traditional middlemen and ensuring artists receive fair compensation. Video platforms like YouTube host tutorials on traditional Mithila painting techniques, democratizing access to this knowledge and inspiring artists far from Bihar to study and adapt the style.

Art residencies, workshops, and cultural exchanges have further internationalized Mithila Art. Mithila artists travel abroad to demonstrate their techniques, collaborate with artists from other traditions, and participate in global dialogues about folk art, women’s art, and cultural preservation. These exchanges enrich both Mithila painting and the contemporary art world, demonstrating that traditional handmade art forms have vital contributions to make to contemporary artistic discourse.

The geographical span of Mithila painting across Bihar and Nepal has created subtle regional variations. While the core aesthetic principles remain consistent, artists from different villages may emphasize different motifs, use slightly different color palettes, or favor certain styles. This diversity within unity makes Mithila Art a living tradition rather than a static museum piece, constantly renewing itself while honoring ancestral techniques.

The Traditional Handmade Process of Mithila Painting

The creation of traditional Mithila painting begins long before brush meets paper. It starts in the fields and forests of the Mithila region, where artists gather natural materials that will become the colors on their canvases. This deep connection to the local environment distinguishes handmade Mithila Art from industrially produced artwork. Every painting carries within it the essence of Bihar’s soil, plants, and traditional knowledge.

Red pigments, essential to Mithila painting, come from multiple sources. The kusum flower yields a vibrant red, while certain roots and barks produce deeper crimson tones. Yellow derives from turmeric powder or pollen from specific flowers. Blue comes from indigo plants that grow in the region. Green is created by mixing yellow and blue or extracting color from bilva (wood apple) leaves. Black, interestingly, comes from soot collected from clay lamps, often mixed with cow dung as a binder. White is traditionally prepared from rice powder or lime. These natural pigments have been used for centuries, their preparation methods passed down through generations of Mithila women.

The tools of traditional handmade Mithila painting are equally organic and locally sourced. Brushes are fashioned from bamboo sticks, their ends frayed to create different line widths. For finer details, artists use matchsticks wrapped with cotton thread. Some artists prefer using small twigs from specific trees, each providing a slightly different drawing quality. For the finest lines and most intricate patterns, artists sometimes use their own fingers, demonstrating the ultimate handmade technique—direct contact between creator and creation.

The surface preparation for traditional Mithila Art varies depending on the medium. Historically, women prepared walls by coating them with a mixture of clay and cow dung, creating a smooth, slightly absorbent surface ideal for natural pigments. When Mithila painting transitioned to paper and cloth in the 20th century, artists had to adapt their techniques. Today, handmade paintings typically use thick, textured paper or cloth that can absorb the natural colors without bleeding. Some artists prepare their surfaces with a thin coating to enhance color vibrancy and adhesion.

The actual painting process follows a methodical approach honed over centuries. Artists begin by sketching the basic composition and main figures using a single color, often black or brown. The characteristic double-line borders that define Mithila painting come next, creating clear boundaries between different elements. These parallel lines represent duality in nature—day and night, male and female, earth and sky—a philosophical concept embedded in the artwork’s structure.

After establishing the outline, artists fill in the major forms with bold colors. In the Bharni style of Mithila painting, these colors are bright and solid, completely filling the defined spaces. Other styles may use cross-hatching, stippling, or line patterns to create color areas. The final and most time-intensive step involves filling every empty space with intricate patterns—geometric designs, floral motifs, dots, lines, and curves that ensure no canvas area remains blank.

The time required for a handmade Mithila painting varies enormously based on size and complexity. A small, simple piece might be completed in a day or two. Medium-sized paintings with moderate detail typically require four to seven days of continuous work. Large, highly detailed traditional Mithila Art pieces can take weeks or even months to complete. This labor-intensive process explains why authentic handmade paintings command prices that reflect the artist’s skill and time investment.

Why does the handmade nature of Mithila painting matter in today’s world? First, each handmade piece is unique. Even when an artist paints the same subject repeatedly, variations in hand pressure, natural pigment consistency, and the artist’s emotional state create subtle differences. Second, the handmade process connects the artwork to centuries of tradition—when you own a handmade Mithila painting, you own a piece of living history. Third, handmade creation supports traditional artisans, particularly women in Bihar’s rural areas, providing them with sustainable livelihoods that keep the tradition alive.

Themes and Styles in Traditional Mithila Painting

Traditional Mithila Art draws from three fundamental thematic wells: religion, social life, and nature. These themes aren’t separate categories but often interweave in single paintings, reflecting the holistic worldview of Mithila’s culture where the divine, human, and natural realms constantly interact.

Religious themes dominate much of traditional Mithila painting. Hindu deities appear frequently, with each god or goddess depicted according to iconographic conventions passed down through generations. Krishna is perhaps the most beloved subject, often shown playing his flute among peacocks and cows, or in loving embrace with Radha. These Radha Krishna handmade paintings capture the divine love story that represents the soul’s yearning for union with the divine. Durga, riding her lion and defeating the buffalo demon Mahishasura, appears in paintings created during the autumn festival season. Lakshmi and Ganesha, deities of prosperity and new beginnings, frequently grace Mithila Art created for weddings and festivals.

Beyond individual deities, traditional Mithila painting incorporates complex mythological narratives. Scenes from the Ramayana, particularly those involving Sita (who was born in Mithila), hold special significance. The Mahabharata’s stories also appear, along with local folklore and tantric symbols that speak to deeper esoteric traditions. These paintings serve as visual scriptures, making sacred stories accessible to those who might not read Sanskrit texts.

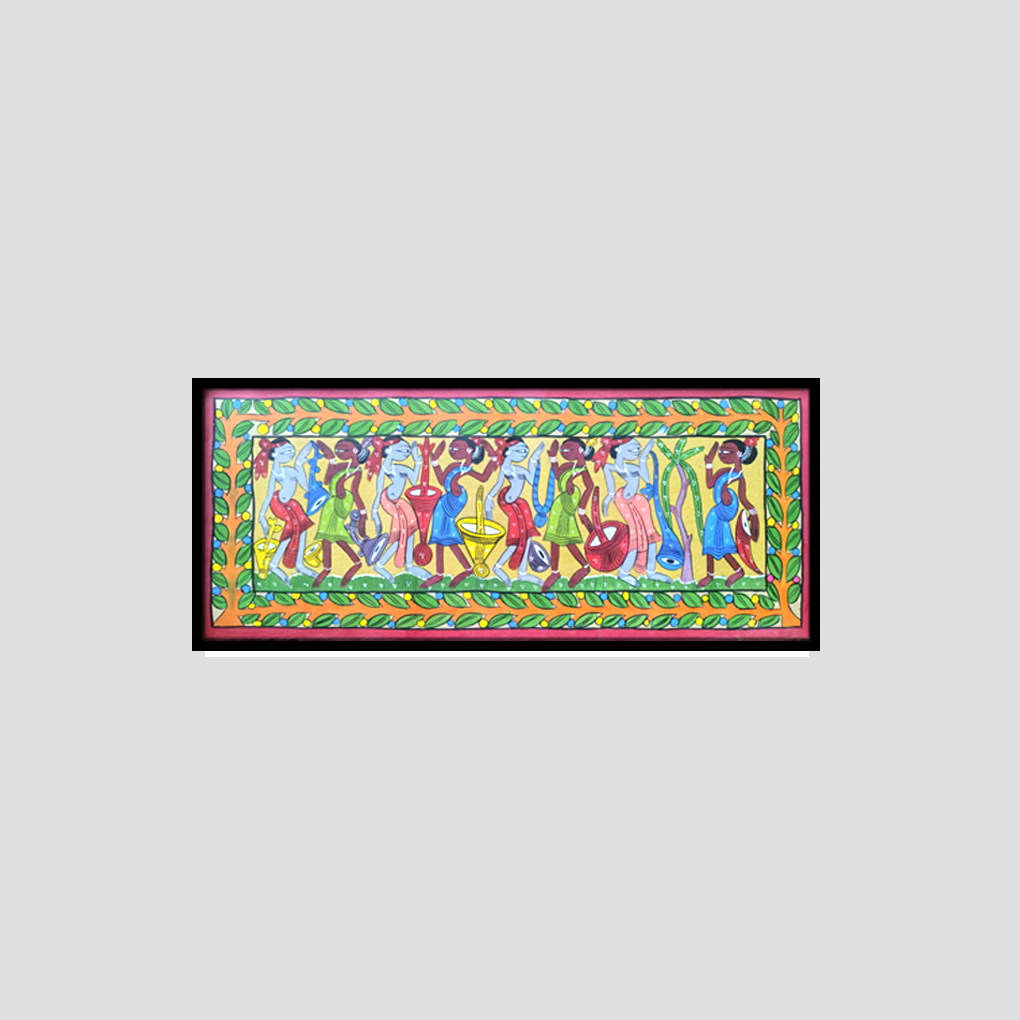

Social themes in Mithila Art provide invaluable windows into traditional rural life in Bihar. Paintings depict wedding ceremonies with their elaborate rituals, women gathering at wells to collect water, farmers working in fields, markets bustling with vendors and buyers, and children playing traditional games. These scenes aren’t mere documentation but celebrations of community life, capturing moments of joy, labor, and social bonding. Wedding paintings hold particular importance in traditional Mithila painting, as marriages represent not just the union of individuals but the joining of families and the continuation of lineage.

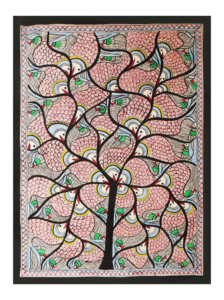

Nature themes reflect the agricultural heritage of the Mithila region. The sun and moon appear frequently, often anthropomorphized with faces, representing cosmic principles and the passage of time. Trees hold sacred significance—the banyan tree with its expansive canopy symbolizes longevity and protection, while the tulsi (holy basil) plant represents devotion and purity. Fish swimming in pairs symbolize fertility and marital happiness. Peacocks, with their spectacular plumage, represent beauty and are associated with Krishna, who wore peacock feathers in his crown.

The five traditional styles of Mithila painting each offer distinct aesthetic approaches, though artists may blend elements from multiple styles in a single work.

Bharni style is the most visually striking and perhaps the most recognized internationally. Characterized by bright, bold colors that completely fill the painted forms, Bharni paintings grab attention immediately. Red, yellow, blue, and green dominate, often in contrasting combinations that create visual vibrancy. This style traditionally depicts Hindu gods and goddesses, particularly in their more elaborate, royal forms. The solid color fills leave no paper showing within the figures, creating a tapestry-like effect. Bharni handmade Mithila paintings often take longer to complete because of the careful color filling required.

Kachni style takes the opposite aesthetic approach, emphasizing fine line work and intricate detailing over color. Traditional Kachni paintings often use just black or brown lines on a light background, though modern artists may introduce limited color. The name derives from “kachh,” meaning line, and these paintings showcase the artist’s skill in creating complex patterns through thousands of delicate strokes. Geometric designs, cross-hatching, and fine parallel lines create texture and form. Kachni style is particularly effective for depicting detailed scenes with multiple figures and layers of narrative.

Tantrik style incorporates mystical and religious symbolism, drawing from tantric traditions where geometric forms represent cosmic principles. These handmade Mithila paintings feature mandalas, yantras (geometric diagrams used in meditation), and symbolic representations of deities and cosmic forces. The Sri Yantra, Kali Yantra, and similar sacred geometries appear frequently. Colors in Tantrik paintings often follow traditional associations—red for energy and passion, white for purity, black for mystery and transformation. These paintings serve not just as decoration but as objects for meditation and spiritual practice.

Godhna style has roots in the traditional tattoo art of the region. “Godhna” refers to the practice of tattooing, and this style translates those tattoo patterns and motifs into painting. It features simple, bold forms with repetitive linear patterns and geometric designs. The color palette tends toward earth tones—browns, ochres, and blacks—though some contemporary Godhna-inspired handmade paintings use brighter colors. This style connects Mithila Art to the broader tradition of body art and personal adornment in Indian culture.

Kohbar style is perhaps the most culturally specific, created for the bridal chamber during wedding celebrations. Traditional Kohbar paintings use predominantly red and white colors and feature specific auspicious symbols: the lotus representing fertility and prosperity, the bamboo grove symbolizing flexibility and strength, fish representing marital bliss, and the sun and moon representing the cosmic couple. Geometric patterns fill the backgrounds, and the overall composition follows traditional layouts passed down specifically for wedding purposes. The entire Kohbar Ghar becomes a sacred space through these paintings, believed to bless the couple with happiness and children.

Understanding these themes and styles enriches the experience of viewing and collecting traditional Mithila Art. When you know that the peacock represents Krishna’s divine playfulness, that the double fish symbolize a happy marriage, or that the geometric patterns in a Tantrik painting represent the structure of the universe itself, each handmade Mithila painting becomes a doorway into a rich cultural and spiritual world.

The Unique Visual Language of Traditional Mithila Art

Traditional Mithila painting speaks a visual language developed over centuries, with conventions and characteristics that make it instantly recognizable. Understanding this language helps appreciate the sophistication beneath what might initially appear as “simple” folk art.

The double-line borders that outline figures and objects in Mithila Art are perhaps its most distinctive feature. These parallel lines, typically drawn in black or dark brown, create a clear boundary between different elements in the composition. But they serve more than a structural purpose—they represent philosophical duality. In Hindu and Buddhist thought, the universe operates through paired opposites: creation and destruction, masculine and feminine, light and dark. The double lines embody this principle, suggesting that every form contains within it the tension and balance of complementary forces.

Color choices in traditional handmade Mithila painting aren’t arbitrary but follow symbolic associations. Red represents energy, passion, and auspiciousness—it’s the color of Hindu weddings and festivals. Yellow signifies knowledge and learning, associated with Saraswati, goddess of wisdom. Blue connects to the divine, particularly Krishna’s transcendent nature. Green represents nature and growth. Black, far from being negative, signifies mystery and the unknown, often used to outline forms and create definition. White represents purity and peace. When Mithila artists choose colors, they’re not just making aesthetic decisions but invoking these symbolic meanings.

The intricate pattern-filling that characterizes Mithila Art follows the principle of “horror vacui”—fear of empty space. In traditional philosophy, emptiness must be filled with creative energy. Every empty space in a Mithila painting becomes an opportunity for geometric patterns, floral motifs, dots, lines, or other decorative elements. This creates a visual density that distinguishes authentic handmade Mithila painting from simpler folk arts. It also means viewing these paintings rewards sustained attention—the longer you look, the more details emerge.

The flat, two-dimensional style of traditional Mithila painting deliberately avoids Western conventions of perspective and shading. Figures don’t recede into space or cast shadows. Instead, everything exists on the same pictorial plane, often with larger figures indicating importance rather than proximity. This flattening creates a decorative effect but also serves conceptual purposes. Mithila Art isn’t trying to create the illusion of three-dimensional space but rather presenting a symbolic reality where scale, position, and proportion reflect spiritual and social hierarchies.

Symmetry plays a crucial role in many traditional Mithila paintings, particularly in the Kohbar and Tantrik styles. Compositions often balance left and right sides, with mirror images or complementary elements. This symmetry reflects cosmic order and balance, the principle that the universe maintains equilibrium through the interplay of opposing forces. Some handmade Mithila paintings are entirely symmetrical, like mandalas, inviting meditation and contemplation.

The folkloric storytelling approach in Mithila Art means that narrative and decorative elements coexist seamlessly. A painting might depict Krishna’s childhood in Vrindavan, with the god as the central figure surrounded by gopinis (milkmaids), cows, peacocks, trees, and geometric patterns filling the sky and ground. Each element contributes to the story while also creating visual interest. This multi-layered approach allows traditional Mithila painting to function simultaneously as narrative illustration, religious icon, and decorative art.

Facial features in Mithila Art follow specific conventions. Eyes are typically shown in profile even when faces are frontal, creating an Egyptian-art-like effect. Noses are simplified to curved lines. Mouths are small, often just suggested. These stylized features aren’t the result of inability to draw realistically—they’re deliberate choices that make figures instantly recognizable as part of the Mithila tradition. The same stylization applies to hands, often shown with fingers extended in mudras (sacred gestures) or holding symbolic objects.

The use of borders and frames within Mithila paintings creates compartmentalized spaces. A single painting might contain multiple bordered sections, each depicting different scenes or aspects of a story. These internal frames help organize complex narratives and also reference the architectural spaces—doors, windows, walls—where Mithila Art traditionally appeared. Even on paper or canvas, the paintings echo their origins as wall decorations.

Regional variations add another layer to the visual language of Mithila painting. Artists from different villages may emphasize different motifs, use characteristic color combinations, or favor certain pattern styles. These variations, while subtle to outsiders, are recognizable to those familiar with the tradition. They demonstrate that traditional handmade Mithila Art, while following shared conventions, also allows for individual and regional expression within those parameters.

From Village Walls to Global Galleries: Mithila Art Today

The journey of Mithila Art from the walls of Bihar’s villages to international art galleries is a remarkable story of cultural preservation, adaptation, and recognition. For centuries, traditional Mithila painting remained largely unknown outside its home region, practiced by women as part of their domestic and ceremonial duties rather than as “art” in the commercial sense.

The transformation began in the 1960s when a severe drought struck Bihar. William G. Archer, a British civil servant and art historian stationed in the region, suggested that the women artists could earn income by creating their traditional paintings on paper rather than walls. The All India Handicrafts Board and various NGOs helped organize the artists, provide materials, and connect them with markets. This transition from wall art to portable handmade paintings allowed Mithila Art to reach national and eventually international audiences.

Traditional uses of Mithila painting continue in many villages. The Khobar Ghar ritual remains central to wedding celebrations, with families commissioning elaborate paintings to decorate the bridal chamber. During festivals, particularly Durga Puja and Diwali, women still paint their courtyard walls with traditional motifs, refreshing these decorations annually. Birth celebrations, naming ceremonies, and other life milestones are marked with specific Mithila Art motifs believed to bring blessings and protection.

However, the evolution to collectible handmade pieces has profoundly impacted both the art form and the artists. What was once ephemeral—paintings on walls that would fade and be repainted the following year—became permanent. This shift encouraged artists to develop more complex compositions and refine their techniques, knowing their work would endure and be judged by audiences beyond their immediate community. The traditional handmade process remained essentially unchanged, but the artistic ambition and scope expanded.

Contemporary Mithila artists are increasingly exploring themes beyond traditional religion and folklore while maintaining the distinctive visual language of traditional Mithila painting. Some address social issues like women’s education, environmental conservation, and caste discrimination. Others experiment with abstract compositions, using the geometric patterns and color palettes of Mithila Art to create non-representational works. Still others blend Mithila techniques with other art forms, creating fusion styles that speak to younger, global audiences while respecting traditional roots.

International recognition has transformed the status and economic prospects of Mithila Art. Major museums worldwide, including the Museum of Folk Art in New York, the British Museum in London, and various institutions in Japan and Europe, have acquired traditional handmade Mithila paintings for their permanent collections. This institutional validation has elevated Mithila Art from “craft” to “fine art,” with corresponding increases in market value and cultural prestige.

Several Mithila artists have achieved individual fame, becoming cultural ambassadors for Bihar and Indian folk art. Sita Devi, who received the Padma Shri award in 1981, is credited with bringing Mithila painting to national prominence. Ganga Devi, another Padma Shri recipient, was known for her innovations while respecting tradition. These and other master artists have inspired younger generations to pursue Mithila painting professionally, ensuring the tradition’s continuity.

The role of social media and online marketplaces in amplifying Mithila Art’s reach cannot be overstated. Platforms like Instagram, Facebook, and Pinterest allow artists to showcase their handmade work to global audiences instantly. Online marketplaces enable direct sales from Bihar’s villages to collectors worldwide, bypassing traditional middlemen and ensuring artists receive fair compensation. Video platforms like YouTube host tutorials on traditional Mithila painting techniques, democratizing access to this knowledge and inspiring artists far from Bihar to study and adapt the style.

Art residencies, workshops, and cultural exchanges have further internationalized Mithila Art. Mithila artists travel abroad to demonstrate their techniques, collaborate with artists from other traditions, and participate in global dialogues about folk art, women’s art, and cultural preservation. These exchanges enrich both Mithila painting and the contemporary art world, demonstrating that traditional handmade art forms have vital contributions to make to contemporary artistic discourse.

Bringing Traditional Handmade Mithila Paintings Into Your Home

Decorating with traditional Mithila Art offers unique benefits that mass-produced art cannot match. Each handmade piece carries the energy and intention of its creator, the cultural weight of centuries of tradition, and the authenticity that comes from natural materials and time-honored techniques. These paintings don’t just fill wall space—they create conversation, add cultural depth, and connect your home to the rich heritage of Bihar’s Mithila region.

Living rooms are ideal spaces for displaying Mithila paintings. The visual complexity and vibrant colors of traditional handmade Mithila Art make these pieces natural focal points. A large Bharni-style painting with its bold colors can anchor a seating area, while a series of smaller paintings can create a gallery wall. The intricate patterns reward close viewing, making Mithila paintings particularly suited to spaces where people linger and converse. Guests invariably ask about these distinctive artworks, providing opportunities to share the stories behind the art form.

Sacred or meditation spaces particularly benefit from traditional Mithila paintings with religious themes. A Radha Krishna handmade painting can enhance a home altar or puja room, serving not just as decoration but as a focus for devotion. Tantrik-style paintings with their geometric yantras and spiritual symbolism create contemplative atmospheres ideal for meditation or yoga practice. The traditional belief that Mithila Art brings blessings and positive energy makes these paintings especially appropriate for spiritual spaces.

Radha Krishna paintings represent the most popular choice among Mithila Art collectors, and for good reason. These depictions of divine love resonate across cultural boundaries, speaking to universal themes of devotion, beauty, and transcendence. In traditional iconography, Krishna’s blue skin represents the infinite sky, while Radha’s golden complexion symbolizes the earth. Their union represents the merger of the infinite with the finite, the divine with the human. Placing a Radha Krishna handmade Mithila painting in your home invites these energies into your space, whether you interpret them spiritually, aesthetically, or both.

Peacock paintings showcase Mithila Art’s ability to celebrate natural beauty through stylized representation. The peacock, with its elaborate plumage, becomes even more spectacular in the hands of Mithila artists who fill each feather with intricate patterns and vibrant colors. These paintings work beautifully in virtually any room, adding movement and life to the space. The peacock’s association with Krishna adds a subtle spiritual dimension, while its inherent beauty appeals even to those less interested in religious symbolism.

Nature-themed handmade Mithila paintings featuring trees, fish, birds, and celestial bodies create calming environments. These work especially well in bedrooms, where their gentle imagery and intricate patterns can aid relaxation. The symbolic associations—fish representing marital harmony, the moon representing calm reflection, the sun representing energy and growth—add layers of meaning that enrich daily experience of these artworks.

The conversation-starter potential of traditional Mithila Art shouldn’t be underestimated. In an age of generic décor, displaying authentic handmade paintings from Bihar’s villages signals cultural awareness and appreciation for traditional crafts. These artworks prompt questions: Where does this come from? How was it made? What do the symbols mean? These conversations can lead to discussions about Indian culture, women’s artistic traditions, sustainable craftsmanship, and the value of preserving folk arts in a globalizing world.

Supporting traditional artisans through your purchase adds another dimension of meaning. When you buy handmade Mithila paintings, you’re directly contributing to the livelihoods of women artists in Bihar’s villages. This economic support helps preserve the tradition by making it viable for younger generations to learn and practice. You become part of a chain of patronage that has sustained Mithila Art for centuries, updated for the 21st century.

Practical considerations for displaying Mithila Art include proper framing and lighting. As discussed earlier, handmade paintings with natural colors require glass-front frames and should avoid direct sunlight. However, they need adequate lighting to reveal their intricate details. Consider using picture lights or positioning the paintings where they receive indirect natural light during the day and supplementary artificial light in the evening.

Grouping multiple Mithila paintings can create powerful visual impact. A collection showing different styles—Bharni, Kachni, Tantrik—demonstrates the range of traditional techniques. Alternatively, collecting paintings on a single theme (different depictions of Krishna, various representations of peacocks) creates thematic coherence while showcasing different artists’ interpretations. The key is allowing each piece room to breathe while creating visual relationships between them.

Consider the color palette of your space when selecting traditional handmade Mithila paintings. While these artworks typically feature bold colors, they can complement both vibrant and neutral décor schemes. Against white walls, Mithila paintings pop dramatically. Against colored walls, choose paintings with complementary hues that create harmony rather than conflict. The natural earth tones common in Mithila Art often work well with contemporary minimalist interiors, providing warmth and cultural richness.

Conclusion

Traditional Mithila Art, with its handmade processes, natural materials, and centuries-old techniques, offers something increasingly rare in our modern world: authenticity. Each brushstroke carries the weight of tradition, each color tells a story, and each painting connects us to the women of Bihar’s villages who have preserved this art form through generations. In recognizing and collecting Mithila painting, we’re not just acquiring beautiful objects—we’re participating in the continuation of a living cultural tradition.

The enduring appeal of traditional handmade Mithila Art lies in its ability to speak simultaneously to the past and the present. The themes may be ancient—gods and goddesses, wedding rituals, natural phenomena—but the execution by contemporary artists makes each piece a bridge between tradition and modernity. The art form has proven its adaptability, embracing new surfaces and subjects while maintaining the essential characteristics that make Mithila painting distinctive.

As cultural preservation becomes increasingly urgent in a homogenizing global culture, supporting traditional handmade art forms like Mithila painting takes on added significance. Each purchase, each appreciation, each conversation about this art helps ensure its survival. The women artists of Mithila have given the world a treasure; by embracing their work, we honor their creativity and commitment while enriching our own lives.

Whether you’re drawn to the spiritual depth of Radha Krishna paintings, the natural beauty of peacock motifs, the geometric precision of Tantrik art, or the narrative richness of social scenes, there’s a traditional handmade Mithila painting waiting to transform your space. These artworks don’t just decorate walls—they tell stories, preserve culture, support communities, and remind us daily of the irreplaceable value of human creativity and traditional knowledge.

Explore our curated collection of authentic, handmade Mithila paintings created by women artists from Bihar’s villages using traditional techniques and natural materials. Each piece represents hours of meticulous work, centuries of inherited knowledge, and the living heritage of one of India’s most treasured folk art traditions. Bring the colors, stories, and spiritual energy of Mithila Art into your home and become part of this

Blog

Get fresh home inspiration and helpful tips from our interior designers